Fall racing is here and I’ve got making weight on the brain!

I trained at 142 pounds, give or take, as an undergrad at Lehigh. When I walked into Undine Barge Club, newly graduated and eager to learn how to scull, the world of club and elite level rowing was still unfamiliar and unclear. Despite this, I somehow maintained the understanding that a 142-pound female sculler probably wouldn’t cut it on the racecourse, at least not on the big stage. From my perspective at the time, I had a choice: Gain additional muscle mass and pursue a career as an open weight, or lean out my frame and race light.

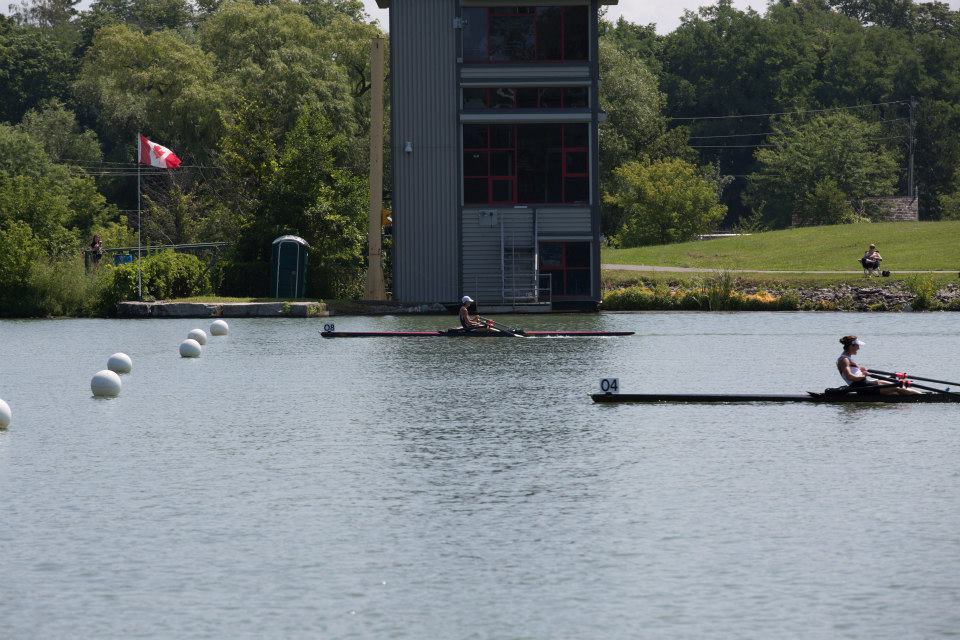

Anyone who’s close to my rowing knows that I chose to race light. Few probably realize that my first time competing as a lightweight was in fall 2011 (Head of the Charles in the light women’s four – we crushed it, finishing second in what’s still one of my all-time favorite races), and my first full season racing lightweight was in summer 2012.

Did you happen to note the timeframe?

I started sculling in 2006. I did not race lightweight until 2012!

The timing wasn’t completely by design: Injury kept me off of the racecourse and mostly relegated to swimming laps in the pool in 2009, 2010 and summer 2011. But, during the preceding three years, racing as a small open weight was the result of deliberate decision.

For athletes naturally on the cusp of lightweight, who may also be relatively new scullers and unsure of what path to pursue, understand one very important point: any fast lightweight can hang with the fast open weights. When I started at Undine, one of the more senior women on the team shared this absolute pearl and for some reason it really resonated. I had been training within 5-7 pounds of max weight, yet wholeheartedly considered “making weight” a distraction and counter to developing speed.

For athletes and other readers who won’t ever have to weigh-in for competition, first, keep reading! You may pickup a pearl of nutritional wisdom or two. Second, allow me to provide some additional context—you may not even know what lightweight rowing is!

Rowing, like weightlifting and wrestling, for example, has weight classes—two, to be exact: lightweight and open. Athletes who naturally weigh within 10-15 pounds of international lightweight standards (59 kgs for female and 72.5 kgs for male single scullers) will sometimes opt to drop body weight and compete in the lightweight classification. With the playing field essentially evened, most rowers will pursue this option intending to yield more competitive results.

Basic Tenets and Timing

There’s no right prescription for when an athlete should “go lightweight,” assuming it’s even a consideration. Training weight, racing weight and overall career trajectories are personal and should be individualized. Yet it’s important to identify priorities early on, and determine how they fit into the big picture and support the larger goals. Plenty of athletes dive into lightweight rowing and never look back. Others successfully toggle between light and open depending on the time of the year. Many others, however, try to tackle the weight-making process too soon or at a time that doesn’t necessarily make sense, and ultimately hurt their careers.

Changing your body composition takes time. Losing weight while working to gain strength and power takes time. If you’re in the early stages of developing boat speed, lightweight rowing may best fit into the picture as an ancillary goal at first—part of a longer-term project and not something you need to rush into as soon as you hit your first major race.

Whether you’re new to sculling and considering lightweight, or experienced and wanting to improve your approach to making weight; an athlete looking to increase performance by manipulating nutrition, or someone interested in bettering their health and wellbeing, the same basic principles apply.

1. Eat real food!

This is fundamental—arguably the single most important nutrition practice for good health. Conceptually, it’s also the simplest yet surprisingly difficult to implement if you’re accustomed to eating heavily processed food.

Unless you have an allergy, there’s no reason to limit what types of real, whole foods you include in your diet. Meat, seafood, dairy, fruits and vegetables, grains, nuts, seeds, natural sweeteners like honey and maple syrup—it’s all fair game as long as it’s in or close to in its natural form. Anything else—what world-renowned food and environmental writer and activist Michael Pollan likes to call “edible food-like substances”—is out… most of the time.

Do I eat some processed and packaged foods? Sure. White rice is a staple in my diet, and it’s rare that a day goes by without me having a GoMacro bar between practices or as a snack before bed. But anything with a long list of additives or ingredients that I don’t recognize won’t ever even enter my house.

Don’t eat anything your great-grandmother wouldn’t recognize as food. –Michael Pollan

2. Think lifestyle, not dieting.

Weighing in for racing only happens a handful of times a year. In practice, it’s a transient task because the very last drop to weight is usually the result of manipulating the type of food consumed during the two to three days before an event. Optimizing performance, altering body composition and establishing a lightweight career, however, involves a long-term commitment to healthy eating. It’s essential to establish sustainable habits, and perhaps a shift in perspective on eating and food.

“Dieting” implies restriction, and is defined by conscious control. It’s a practice with an endpoint and a word with a negative overtone. Lifestyle, on the other hand, is the way in which we live. With regard to nutrition, this means healthy eating and eating for performance are the norm. The idea of control or constantly having to choose between “good” and “bad” foods is minimized; foods that were once “good choices” become second nature and part of the daily routine.

3. Tackle one change at a time.

From a practical standpoint, implementing changes one by one lets you to focus your energy and create momentum in a concentrated way. In addition, single changes are manageable! It doesn’t get much simpler than committing to eating more greens, for example, or packing a lunch during the workweek instead of eating on the go, and then nurturing that commitment until it becomes routine.

From a performance perspective, single changes let you observe how your body responds in terms of energy, output, recovery and sleep. Self-awareness is essential to athletic success, and what you eat has a direct impact on how you feel. Likewise, nutrition is incredibly personal—what works for one athlete may completely derail the performance of another. Keep tabs on how you feel as you as you adopt new habits and try new nutrition practices and food. Make adjustments accordingly.

A Case for Counting Macros

A teammate recently asked if I follow a specific diet. The answer is “yes” and “no.” I’ve dabbled in everything from vegetarian to Paleo protocols, mostly just for fun, and pored over books ranging from The Engine 2 Diet by Rip Esselstyn to The Paleo Solution by Robb Wolf. I like to experiment and learn what I can. But I also have celiac disease – I eat gluten free by necessity, and otherwise indulge in anything wholesome and real.

While not a diet in the traditional sense, I also count macros, which means tracking the number of grams of protein, carbs and fat (i.e., macronutrients) consumed daily. The practice had been trending in the CrossFit community. I became curious, and so consulted with a nutrition coach and ran. It’s been roughly 14 months since I started. I’m still tracking and have become a big fan.

Top Two Benefits

Macro counting: 1) eliminates the guesswork when making weight, or fueling for practice and racing, and 2) gives you specific, short-term targets and goals. The mind can easily turn negative in the third 500m of a 2k, and no athlete needs a voice in their head saying they needed more food to perform. In addition, making weight can feel challenging at best and exhausting at worst, particularly if you easily fluctuate. Counting macros lets you focus on specific, small targets instead of one large, looming number on the scale.

As a rower who needs to make weight for racing, an athlete whose body is extremely sensitive to food choices and fueling needs, and an individual with an affinity for detail, counting macros has been a great fit. But the practice is not for everyone. If you instinctively balk at the idea of tracking your food, macro counting is not for you! If you’re curious or naturally drawn to the practice, educate yourself, talk to a pro and have fun.

Final Thoughts

Racing and competition weight for many types of athletes is different than training weight. High-level endurance athletes like runners, cyclists and triathletes, as well as strength and power athletes like weightlifters, compete at weights both individualized and optimized for performance.

That said, making weight, in rowing or otherwise, adds an entirely separate component to race preparation and training. There’s time, planning and energy involved that’s separate from typical demands. It’s easy to get preoccupied with weigh-ins and weight, which is why I advocate speed and skill first. Learn what it’s like to really move in the single, and then tackle the lightweight scene later on!

Cara, loved, loved, loved this post (and not just because my mug made a cameo)! It’s taken years and years to become wise about nutrition but I’m finally there with you. This is such a great lesson to not only rowers but to any athlete, whether recreational or elite. Thank you for sharing your journey thus far.

Jess, thank you for the comment! I’m happy to hear you feel good about your nutrition. It’s amazing how food choices and fueling needs can become such a source of stress or confusion for people. I’d love to do a follow-up post with more detail. The points were pretty basic but that’s where we all need to start, right?! Anyway, glad you enjoyed the read, I hope others do too. I had tons of fun looking through old photos, btw!